I sit at the edge of the parsley patch, out of sight of my grandparents’ house, and slowly munch my way through the vibrant crop. The bitter green leaves have the flavour of spring sunshine, sharp-edged and warm. The thick lawn slippers my grandfather’s feet and I am deaf to his approach. His shadow falls across the parsley and makes me jump. I look up, guilty, expecting rebuke.

“You’ll never get through it all.”

His smile is rare. Carefully, I smile back, a bunch of pre-picked green clutched in one hand.

“Don’t spoil your appetite.”

I watch his back as he works his way around the garden on his regular morning inspection. And slowly push the fat bunch of parsley into my mouth—I continue to chew.

Some memories are tied forever to places, smells, flavours, objects, even low-growing herbs. They return unbidden every time you pass a certain corner or catch the warm vanilla scent of orange blossom. Often, you don’t catch the whole memory, only a hint of something heavy or joyful as it flits through your consciousness.

Parsley makes me think of my grandfather. His short, shuffling stature and wide lipless smile. Of his immaculate garden in antipodean sunshine, his sandals and socks. His entirely predictable irritation at my love of dining by candlelight. Wassis? Can’t see what I’m eating. Of the retirement house he shared with my glorious grandmother who laughed like a cackling drain and chain-smoked through her days in retirement-issue nylon slacks.

And of being abandoned left by my parents while they travelled south with my brother. Of being told that the rough roads of the South Island would make me too sick to enjoy the journey. That I’d spoil the journey for everyone else if I came. And that it was my duty to spend time with these two old people who I didn’t know, to be kind and helpful and good.

At night, I cried into my pillow, thinking I couldn’t be heard, hoping I might be. My grandmother wandered in and gently put her hand on my back. I know now that she understood, but then she was a stranger. An old woman, in an unfamiliar house, in an unfamiliar part of the world.

Parsley is at once joyful and reminiscent of the smallest of mini rebellions, of unexpected love and tolerance, and tinged with an ache of loneliness that persisted through childhood, bleeding into adulthood unchallenged.

I don’t have any photos of this time with my grandparents. My father, the family archivist, wasn’t there to record those moments. Which makes me realise how many of my early memories are reinterpretations of my father’s stories. Stories buoyed by photographic evidence, where every image is captured through his eyes.

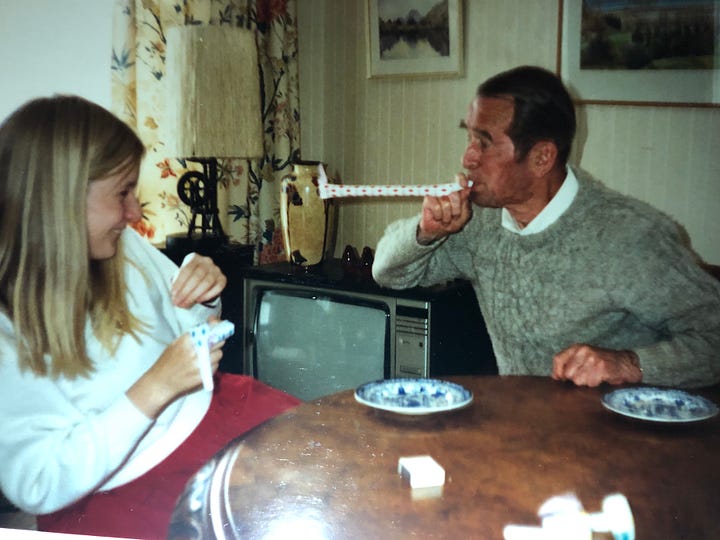

I scour the few photos I do have of my grandparents house for clues. There’s the pair of red glass 1960s birds on top of the television that now live on my father's own mantelpiece. I remember these on top of my grandmother's piano. But of course that’s not right. My grandmother didn’t allow anything—ornaments, dishes, keys—on top of the piano lest they scratch it. Maybe there was a mantlepiece. But where?

Then there’s the silver and blue glass tableware—rare and precious as a kid but which I now find regularly at car boot sales and in junk shops. The table lamp with the spinning wheel stand. The kitchen and ceramic sink that overlooked the garden and the garage and behind that—the parsley patch.

My grandmother was a great believer in soaking dishes. Even as a kid, I’d have preferred to just get them done and out of the way—anxious that I’d be reprimanded for laziness if I didn't.

But this was my grandmother’s house.

“Put some hot water in and leave it. I just wash the ones that’s don’t need soaking. It’s your granpa’s job to finish off and put away.”

She pulled a fresh cigarette out of the packet and caught my shocked expression. She cackled. And lit up.

“Come on. Let’s find something else to do.”

I wish I’d known my grandparents better. Living 12,000 miles apart, the only consistent contact we had was via a crackly phone line with a painful 2-second delay. I tried to avoid these phone calls and the stilted, obligatory conversations. How’s the weather? Fine. How’s school? Fine. The discomfort made worse by the position of the only phone in the house on the wall in the hallway—where our conversation was scrutinised and egged-on. Flapping hands exhorted me to say more, to be more, to compensate for a distance not of my making.

When the phone rang on a Sunday evening, I’d sneak upstairs and make myself too busy to talk. But I couldn’t ignore the summons for long. After an agonising moment where I considered the possibility that maybe, just maybe I could pretend I hadn’t heard, I'd drag myself back down the stairs. Standing static, eyes filled by William Morris wallpaper that rambled across the hallway. Watching myself being watched from the corner of my eye. Waiting for the moment when I could reasonably pass the phone to my brother and escape.

It can’t have been any easier for my grandparents. They didn’t know us any better than we knew them. They died before I had a chance to know them as an adult. My grandfather from complications related to emphysema. My grandmother in the home she'd moved to not long after.

"Of course, you know she killed herself. They found her with her dressing gown cord around her neck."

My mother told me this the way she delivered all Big News.

Here it is. This is yours now. Deal with it.

Small snippets of information that encompassed major events. Information that once I knew, I was supposed to process alone, handle alone and from which I could move on alone. This was her usual method of imparting bombshells.

It was the same way she told me about my father's one-time infidelity with a colleague who I'd adored.

"Of course, you know she had an affair with your father?"

It was the opening "Of course you know ..." that crippled me. It ended the conversation before it began. Of course I didn’t know. But how could I disagree? If I did, I'd make the conversation about something other than what it should have been about. Either way, the conversation would end before it began,

Here it is. This is mine now. I'll deal with it.

Of course, what I do know now is that this was my mother's only way of dealing with her own pain. She didn't have the tools to deal with it and so she handed it on unfiltered.

And I’m left with acres of regret. For the conversations I never had. The questions I never asked. For missing the grandparents I loved without ever really knowing them.

Is there anyone from your past you wish you’d got to know better? Anyone you with whom your relationship feels unfinished? Meet me in the comments.

This was very beautiful to read, but also sad. I think it's so sweet that parsley reminds you of your grandad, what a wonderfully weird thing! You clearly have a lot of lovely memories with them both. I sadly lost all of my grandparents in my first few years of life, so I never knew them, but I have photos of them with me though. So even though I didn't know them, they knew me, and I guess that fills me with some joy. But I so wish I knew them. I think everyone needs a grandparent in their life. There's a lot that you've shared that I can relate to, particularly with the trauma you have from moments in life, and being able to notice your mother's own trauma with how she responds to things. I'm glad you're able to share these things, it helps so much for people who are all going through the same thoughts. We're all human and these are human experiences. So thank you for sharing.

such a poignant and beautiful piece Miranda. I relate to so much of this - your memories are precious and now frames like little oil paintings of words that endure the course of time..