Friends, Readers, Substackers,

This isn’t the post I was intending to send to you today. I planned to write to you about consistency, its lack, and about embracing the fallow periods. It was an exploration (explanation?) of why, repeatedly, I make promises to myself and others which I then fail to deliver. A follow up to my last post but one, where I made another ludicrous promise to myself that I’d change my life in the final year of my forties, by magically changing the habits of a lifetime.

Can you guess how that’s going? Probably.

But as ever, one idea bled into another, channeling multiple rivulets that each had their own idea where I should go, what I should say, how I should frame stuff. That post is still in the works. It’ll come. Once I’ve worked out the kinks and figured out what I actually want to say.

This post—the one that’s at the end of this introductory ramble—is kind of related. It’s about trying one thing that makes you uncomfortable and seeing where it takes you. In my case it’s audio recording my own Substack posts/emails. If you’re listening to the audio version of this post, this is already getting kinda meta.

I think you’re saying “Beckenham”

Before home internet access was common, before smartphones were a thing, if you wanted to know the screen times for our local cinema you had two options—check the listings in the local paper, or call a pre-recorded information line.

This was pre voice recognition, when machines taking over human jobs was still a distant dystopian fantasy. The information line for our local Odeon was a recorded recitation of every film showing that week, read by the cinema manager—a man whose monotone voice betrayed zero excitement for any of the films on offer.

A new recording was released every Thursday for the week ahead. If you wanted the times for a particular film, there was no way to skip ahead, no robot you could ask to short cut you to the information you needed. You had to listen to the whole damn thing. If you drifted and missed the bit you wanted, you waited until the end when the whole thing would repeat—and listen again.

Apart from that one time when the phone was answered by the manager. The same bored voice from the recording. Not recorded though. Live. A real human. I wasn’t prepared for a conversation and stumbled, tongue-tied, through a brief but painful exchange.

Hello. Bromley Odeon.

Uh. Is this the Odeon?

Yes.

Bromley?

Yes.

Oh. Sorry. Umm. I wasn’t exp—I was expecting the recorded film times?

We haven’t updated them yet. Shall I read them to you?

So he did. And I didn’t take in a word he said. I was too bewildered to ask him to repeat himself. Instead I thanked him and hung up.

I think we went for pizza instead.

Then came voice recognition. Or an early, fallible iteration of voice recognition. All the local phone lines were replaced by a single central number and recording—a voice as excessively chirpy as Mr Bromley had been bored—that asked you a question then ignored your answer.

Welcome! To the Odeon Film Line! Please say the name of the cinema you require.

Bromley!

I think you’re saying “Beckenham”. Is this correct?

No?

Please say the name of the cinema you require.

Bromley!

I think you’re saying “Beckenham”. Is this correct?

F’fucksake. Forget it. We’ll get pizza.

These days, recording yourself for broadcast is an everyday thing for a lot of people.

I was going to say “most people” but I’m not sure that’s true. I suspect, despite the quantity of people who record and publish their every thought, these loud voices are probably small in number compared to the majority who still live in relative silence. But how would I know for sure? The quiet ones are so quiet I’ll probably never know.

When I pause the current day onslaught of content, media, noise and chatter for long enough to reflect, I wonder at the bravery of that cinema manager, an early pioneer, recording his own voice every week and, presumably, listening back to that audio. The idea fills me with horror.

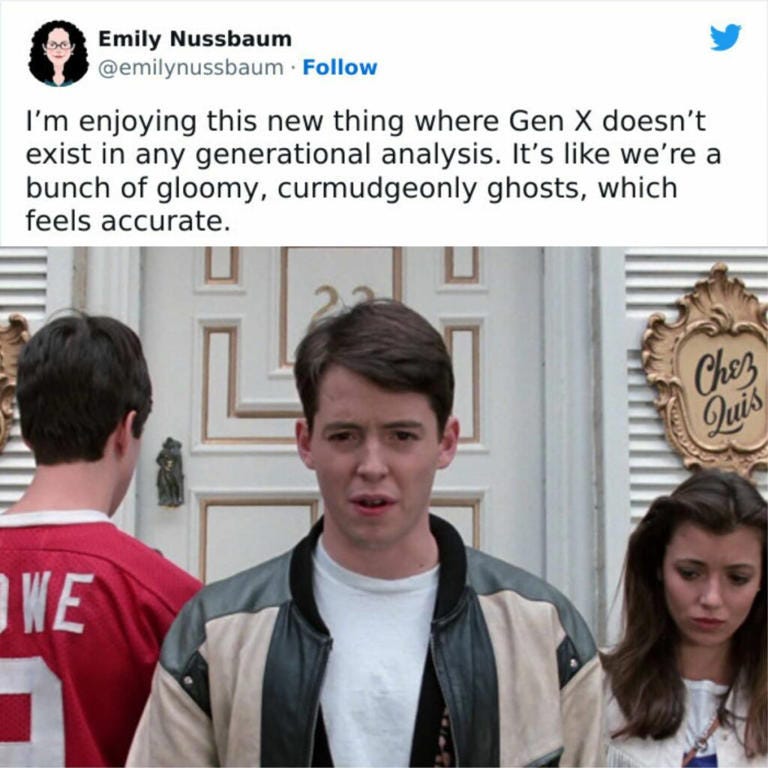

I’m not part of that silent generation raised to be seen and not heard. Neither am I part of the modern generation raised with a mobile recording studio in their pocket in the form of a smartphone. I sit squarely in the middle—where Generation X marks the spot. You know—the invisible, forgotten generation? The ones left out of the generation wars memes, except as a side note, a joke, the ones who, for the most part, don’t bother broadcasting our every thought because we that know no one fucking cares what we think.

When we Xs were in our most impressionable years, no one ever heard their own voice. Broadcast technology was only for professionals—that small subset of adults—musicians, storytellers, actors and journalists who had “made it”.

The first time I heard my own voice must have been when my father bought a dictaphone so he could send recordings of family conversations to his parents in New Zealand. I probably heard them once before they were posted off to the other side of the world—and never head them again.

Until, when I was helping my father pack four decades of life into boxes for a house move, we came across the tapes—salvaged from his own parents’ home after their deaths. I was probably eight years old on these recordings. I listened back to them and winced.

Daddy, why’re you recording me?

A prim child’s voice, like something from an RP Pathé news reel of the 1950s, shrills at me through magnetic tape.

It’s for Granny’n’Grandpa.

Why?

Because we don’t get to see them and it’d be nice for them to know you.

There’s a silence after his explanation. Dead air. As though small me is processing this, unsure what to do next.

Did I really sound like that? So—squeaky? The horror of hearing my own voice hasn’t lessened as I’ve got older.

For a while, I dismissed this horror as normal and universal among us GenXers. I presumed that younger generations, those who learned to broadcast their own voice as children, had adapted early to the dissonance between head voice and real-world voice.

But I’m not sure this is entirely a generational thing. Many of my contemporaries are quite happy to record a voice note or go live on Facebook (and now on Substack). Others talk about the benefit of “writing” as they walk by recording their thoughts on an audio app. This baffles me. Not just the idea of listening back to my own voice which is appalling. But the idea of speaking aloud when there’s no one to hear you, in that moment, but you? That’s just weird, man.

An online course creator recently suggested that we, her students, send our readers voice notes to “connect”. When I balked at the suggestion—highlighting my discomfort with recording myself—another student chipped in with—

It’s easy. It’s just like taking a selfie.

A selfie?! I’m sorry—but we are not speaking the same language, kid.

And can we please not talk about the thousands of pounds I’ve spent and the number of online marketing courses that blithely model their entire programme around selling through fucking webinars.

Maybe it’s because I wasn’t raised to use my own voice. As a kid, I was constantly embarrassed by the volume and tone of my father’s voice. He bellowed his side of our conversations in public, spoke sharply to strangers, harangued shop assistants—and I shrank my own voice in response—which only aggravated him.

Speak up!

—a frequent command that had the opposite effect. Instead of speaking up, I kept my thoughts to myself and didn’t speak at all.

It still doesn’t occur to me to speak aloud a lot of the time. What I have to say doesn’t seem important enough or valuable enough to demand people’s attention. I prefer to write it down—to give people the option to opt out.

So why on Earth did I decide to start recording my own Substack posts? What’s shifted that makes this most uncomfortable of tasks even possible? Honestly, nothing’s changed. Recording this and my last post is and was excruciatingly painful. My breathing gets tight. I stumble over my own words and I have to take frequent breaks to relax my own breath before I continue. Editing out those stumbles is as much about editing out self-critical thoughts.

But I’ve realised how much I appreciate it when other people do the same.

That silent kid was a voracious reader. The slightly more gobby adult I’ve become sometimes struggles to read, but consumes a huge volume of audiobooks and podcasts—delicious indulgences and ideas that melt into my brain like sweet chocolate while my hands and body are engaged in something physical and non-thinky.

And maybe it’ll be uncomfortable for a while. Maybe I’ll get overwhelmed by the gremlins that tell me no one wants to read what you have to say, they certainly don’t want to hear you. Or maybe I’ll get over myself. Maybe the process will ease a little each time I do it, just enough that a year from now, maybe, I’ll be able to look back on a body of writing and reading and notice a distinct shift in my own attitude.

Maybe I’ll find my own voice at last.

p.s. Even the dog isn’t used to me speaking out loud to myself. When I was recording the audio for this post, he popped out from under my chair to stare at me with his head on one side—totally confused about who I was talking to. Then he licked my nose.

Okay. Here’s the deal. You should always record your pieces. I can’t even begin to list all of the whys. You’re a brilliant reader. Funny as fuck and endearing as can be, and your voice and ability to do characters is fabulous. Keep doing it and do, pet, try to get over the fear and embarrassment(?) because if you don’t, you’ll be withholding some thing beautiful from your audience of readers and listeners. The beautiful thing? You.

Wonderful! Weirdly this was the first Substack I have actually listened to. Spooky! Keep talking because you read so well and I will always opt to hear you from now on! I particularly loved the Bromley Odeon conversation