Twisted Roots

A journey from London to Shropshire to New Zealand—to unearth how my reality has been shaped by my family's history.

London, 2011-2013

“D’you want to know what I think of you? You're selfish. You're a selfish bitch. You ruined your brother's wedding and his graduation. That was my day. You shouldn’t have even been there. It was my day and you ruined it. You ruined that and you ruined his life!”

I’m standing in the small middle room of my small home in South London, holding the phone five inches from my ear, my head tilted slightly to one side while my mother escalates to a screaming pitch—trying to make sense of what’s happening.

While my mother rails at me, unfolding a bitter catalogue of my lifetime of failures as a daughter and as a human being, I detach. Think—this is odd. And I think back to my brother’s graduation.

I remember it was hot. Cambridge was full to bursting as thousands of graduates and their families converged in the narrow streets and scattered to their various colleges. I remember my mother being stressed, hurried. Flighty. Filled with anxious pride.

I also remember being ill. I was in the midst of teenage glandular fever. I was exhausted and could barely walk. That morning, I’d woken with a pin-prick rash that covered my entire body. I probably shouldn’t have been there—she’s right about that—but I wanted to be there. For Sam, my brother.

I was hot, dehydrated and I had no water. I’d had no water since we left London. I had asked, repeatedly, to stop so I could get water. We hadn’t stopped. By the time we reached the college grounds, my head was pounding, the rash had climbed up and over my neck, I was feeling sick and feverish and was barely holding back tears. I’ve never been any good at holding back my tears. When they want to come, they fucking come.

Only then did she look back at me. She caught my reddened eyes, the rash that now covered my face, and flushed in disgust.

“This isn’t about you, you know.”

On the phone, she’s winding down, running out of steam. I’m not arguing back. I can’t. I’m too stunned. What she’s thrown at me is too bizarre. Too—unreal. She’s blown up at me before. But this is something new. This is extreme. This is not normal.

And then something clicks. From nowhere, a bolt of reality.

This rage—this madness—is not my responsibility. This is not me.

It had never been me.

Two years later, my mother had a stroke.

I’d started to test new boundaries. To see how long it would take, if I didn’t rush to her rescue at the first call, for her to figure out a solution on her own.

My partner and I were driving to a glass making class in West London when I got a panicked call from my dad. Did I know where my mother was? She’d left a him a voicemail to say she thought she’d had a stroke but now wasn’t answering her phone. Should he drive up to Oxford and find her?

Three hours later, we tracked her down when a neighbour phoned to say she was home again. She’d decided the best thing to do, after leaving my dad a message to tell him she’d just had a life threatening medical episode, was to pop off to the cinema.

Since that phone-call, and as I’d become increasingly wary of her crises, I’d learned to disconnect and observe before leaping to action. I’d started to test new boundaries. To see how long it would take, if I didn’t rush to her rescue at the first call, for her to figure out a solution on her own. It never took her long, but every time I disengaged from my role as rescuer, my position in the family dropped another notch.

She was still the lynchpin of the family. Everything went through her. My parents legally separated when I was ten, but had never ended their codependent dance of dysfunction. And because I was no longer stepping into my allotted role, my father’s anxiety about her behaviour began to replace mine. What he thought were new and concerning behaviours, I thought were her normal. After the stroke, he attributed every behavioural aberration to this legitimate affliction.

My own pain was multi-layered. I could see my dad struggling. I had to resist rescuing him from the job he was being pulled into, while still resisting the temptation to slip back into that role myself. With each disengagement, my distance from the rest of my family deepened. When relatives visited from New Zealand, my mother would tell me about it the day they left. She sent me photos of the whole family (my father, brother, sister-in-law and tiny niece included) inside emails telling what a lovely time they’d all had and that it was such a shame I couldn’t be there.

But I hadn’t been invited. I hadn’t even known they were in the country.

I found myself stepping back from the wider family, uncertain of what they’d been told but certain that whatever that was, it would be couched in extreme care and sadness. That I would only ever be the villain; the heartless, selfish bitch, who had abandoned and had no interest in her family.

To everyone she met she said—

“I’m really nice now. Everyone tells me I’m much nicer since the stroke.”

I wanted to believe this. I wanted to believe that the stroke had somehow disabled that unpredictable hair-trigger that used to flick her from solicitous to rageful. But I, cautious of everything my mother said and did, didn’t even believe in the stroke.

Shrophire, 2018

Five and a bit years ago, in a tutorial on an Arvon’s life writing course, I was still struggling to find a shape for the story I had been trying to write since long before that painful phone call. The tutor’s flippant observation cut to my heart.

“It’s ironic. You’re trying to tell your story, but really you’re still telling hers. I wonder, what’s your story?”

Before the phone call, I’d been back to New Zealand twice to explore family history, to write, and to find the bones of a place I felt in my soul but where I had spent very little time. I went once with my mother, then again three years later on my own. But when I went alone, I followed the path we’d taken together. I retraced our steps, staying in the same towns, sometimes even the same motels and campsites.

I was still trying to tell her story. To find clues that would help me make sense of who she was when I should have been looking for myself.

The girl with no identity of her own.

This is who you are

Depression is our family inheritance and our shared identity. It’s a comfort blanket that, for many years, bound us all together in mutual and inescapable misery.

My mother revelled in her own depression. She told me once, a wisp of romance in her eye, that she probably had undiagnosed bipolar. But she didn’t need a GP to tell her this or prescribe appropriate medication. No one could tell her anything she didn’t already know. And it was only other people who found it a problem.

"It must be very dull to live all your life in one world."

She forgot the pain of her transition from reality to dreamland once she was there.

Our collective pain provided the evidence she needed that this was not a choice she could make. This was entirely genetic.

There were good days of course—days when she would turn up the radio and sing along to Bob Dylan at the top of her voice, grabbing me by the arm to swing me around the kitchen in a swirl of joy. Days when we would walk through the local wood collecting blackberries for a crumble and laughing as our elderly Labrador grabbed whole mouthfuls of berries from the pot. But always, I held the unspoken knowledge that the bad days would certainly follow.

I walked a tightrope of anxiety. Uncertainty about exactly when it would happen—when she would turn one-eighty degrees and begin scattering blame or worse, switch off, turn away, refuse to respond to me at all—made every moment of unfiltered joy even more precious.

She was determined that Sam and I should join her in her depression. Our collective pain provided the evidence she needed that this was not a choice she could make. This was entirely genetic.

When Sam phoned home from Cambridge, overwhelmed by anxiety, loneliness and the pressure of no longer being the only kid at the top of his class who passed every exam with top marks while spending his revision time playing computer games—when he needed reassurance, a hug, someone to tell him he didn’t have to be first in everything— I’m sure my mother said all the right things.

But afterwards, to me, she said—

“He’s so depressed. If he really wants to kill himself, maybe it would be for the best.”

As a young teenager, struggling with the extremes of school bullying and feeling I had no one on my side, I sat in my own bedroom and howled with loneliness. My mother looked around the bedroom door and said,

“This is who you are. You’re depressive. You'll get used to it."

Then she left.

Years later, I laid myself bare to my partner and together we wept for the little girl who wanted nothing more than a hug and reassurance. The little girl who didn't deserve to be damned. I offered the story as stark warning against getting involved with someone as damaged as I. In return she offered a simple question—

“Are you sure this depression is yours?”

And I wasn’t. I wasn’t sure at all.

The Island, New Zealand, 2005

It’s still light enough to see our way across the sand to the water’s edge. We strip down to our togs—ready to go. Running across the sand, I predict the cold shock as I plunge in and the water strikes my chest. Tight with anticipation, I hold my breath and dip my head under the water, my cheeks bulging with reserved air as I pull through the water and away from the shore. Surfacing, I turn my back to the land and the orange glow from the lone restaurant, and gently scull into the grey where sea and sky merge with only the ripples of the water to define the join. The water is soft and velvet smooth. As I acclimatise to the temperature, the gentle movement of water is soft across my skin. The clear air is as intoxicating as I remember. This the strongest drug I know and one that is absent in my London life.

Separated from the main beach by a protruding cliff wall, this small enclave retains some of the quiet for which we have been searching all day. This is the first time that a part of the island has come close to the place I remember from my childhood. It’s almost two decades since the island of my childhood. In raw daylight, tarmac roads, traffic jams, expensive restaurants, vineyards, and the modern Auckland-style homes of the wealthy have overlaid the forgotten backwater I remember and love.

Tonight I will cry myself quietly to sleep like the child I was—grieving for my beloved island. The place that has lived in my memory for so long no longer exists.

There are intersections now where we have to stop and wait for traffic to pass. And traffic lights! My frequent exclamations of shock make my mother laugh out loud. The humidity too takes me by surprise. Only 48 hours ago, it was mid winter. Crisp cold had frosted the same fingers that now bathe in antipodean waters.

In the twilight, with my back to the electric lights that flood the beach, I am eight years old again and swimming with my cousins in our private paradise. But of course, that never happened. At eight years old, I would never have been allowed to swim at night. And we would never have been as quiet as we are now. But the soft evening, allows me space to reimagine what never happened.

Tonight I will cry myself quietly to sleep like the child I was—grieving for my beloved island. The place that has lived in my memory for so long no longer exists. Maybe it never really did. It was an idyll, conjured from the few weeks I spent here, scattered across a distant decade, in the company of cousins and grandparents long gone, and augmented by the memories and stories of my mother.

What must it be like for her? The changes my mother has seen are far more extreme. Even before we reached the island, she was heading to that vacant, wandery state that I alternately laugh at and am exasperated by.

At the petrol station, she removed the nozzle from the tank without letting go of the pump handle and covered herself in petrol. She was reluctant, but I insisted that this necessitated a journey back to my aunt and uncle’s place for a shower and change of clothes. We were greeted on our arrival by my aunt’s loud and amused horror at my mother’s accident.

“Oh, my GAAARD!” is all my aunt said aloud, but internally I felt the judgement. I trod a fine line between expressing my own exasperation and defending my mother. I am well trained as her protector. I know it wasn’t deliberate. I know she is anxious and excited. I know her hands and her body don’t always keep up with her mind, even when her mind is clear.

My mother scuttled off to clean up and soon we were on the road again, heading for a later ferry and semi-hysterical with relief when we finally land on the island, even if neither or us truly recognise it.

My earliest memory, at the age of five, is of standing on the balcony of my grandmother’s A-frame island house, built for her by my uncle and painted a shade of brown that physically pained her, staring at bananas growing on a real-life banana tree, tantalisingly out of reach.

It was only now, twenty five years later, when planning this trip back to New Zealand, that I learned my mother hadn’t lived her entire childhood on the island. She visited her grandparents here every summer, but only moved to the island when she was fifteen. She spent her life up to that time on another coast—in a town 350 miles and two days drive away on this far edge of the North Island.

But it’s the island that has always been home. It has been a touchstone by which all other places in the world are measured. For my mother—and for me.

Hawkes Bay, New Zealand, 1944

My mother should never have been born.

Her own mother, Elsa, let this slip, speaking aloud what should have been a silent memory. She repeated the story as evidence of her own motherly sainthood, failing to see the damage she inflicted with this careless information.

She told my mother about the doctor’s fury as she lay in the agony of labour and kicked the blocks out from under the bed—

“She should not be having this baby!”

She told my mother too of her own halo-ridden response.

“If this baby wants to be born, then it will be born.”

Only this baby hadn’t been this baby. It had been two. A botched and then illegal abortion left my mother to be born alone.

Wanted or not, my mother hung on with a strength of will that dominated the family’s lives. When she finally arrived she was determined that everyone should know. From the moment of her birth, my mother shouted. She shouted for attention, for affection, for anything and everything that she thought she should or could shout about. Until Elsa, a woman who had previously made a career of frailty, began to shout back. It was a pattern that persisted until the end.

Another time, Elsa told my mother of the carelessness of a neighbour who, on hearing about her loss said:

“A miscarriage? Oh why didn’t you tell me, dear? I could have sorted you out with a knitting needle.”

I’m sure that my mother was loved. But I’m not sure that she felt it. That childhood rage never left her.

Hawkes Bay, New Zealand, 2005

My mother and I are back in the small Hawkes Bay town that was her home until the age of fifteen. Wairoa gets its name from the river the runs around three sides of the town “Te Wairoa Hopupu Honengenenge Matangi Rau” which in Maori means “the long water which bubbles, swirls and is uneven”. The name is apt. The river is broad and fast-flowing. It and its constantly shifting sand bar have a fierce reputation.

We’ve done everything we can to avoid what we’re here to do. But there’s really not much in town to offer distraction. We’ve seen the outside of the house where she used to live and the school she use to attend. We’ve walked the route from one to the other and stopped to sniff the buttered popcorn flowers of the kōwhai. We’ve visited her one remaining school friend who drove us a short way into Te Urewera, as far as Lake Waikaremoana, skittering all the way on the worst roads I’ve ever driven. And we’ve been to Osler’s, the best pie shop in New Zealand, to indulge our shared pastry habit.

I offer to go in with her but she waves me off and, before I can offer again, she bundles out of the car.

So now we’re here. In the car park outside the small hospital, debating whether or not to go in. It’s a low two-storey building, clad in soft lemon yellow. The car park is quiet and nearly empty. We sit for a moment in silence, staring at the building.

“I came here two years ago. When I was in town for the school reunion. A nurse said she’d pull the records out for me.”

“I didn’t know that. Didn’t she find them?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t come back.”

“Why not?”

“I ran out of time.”

We wait.

I offer to go in with her but she waves me off and, before I can offer again, she bundles out of the car.

She’s inside the hospital for a long time. When she finally gets back, she’s shaky. Excitable and anxious.

“I saw the same nurse I saw last time. She remembered me! She found the records years ago and has been holding on to them in case I came back for them.”

But the records aren’t exactly what we expect. A single sheet of paper records not a termination but a still birth. We speculate that this must have been be to protect the doctor involved from prosecution.

But there’s another surprise. The sex of the baby is recorded as male. Not female. Not the sister my mother used to dream about.

She cries briefly then, allowing a lifetime of unexpressed grief only a few wobbly tears and a trembling bottom lip before she dehydrates her own eyes through sheer will.

Our next stop is just next door. The cemetery. Now that she has the paper, my mother is cautiously keen. We know it’s a long shot, but as we’re here we may as well look.

Sited on a hill on the edge of the town, the old cemetery has filled in fits and starts, pushing out the surrounding bush. The cemetery’s population now outnumbers the town’s current inhabitants and as the dead have encroached on virgin turf they’ve opened up patchy views over on the ever-approaching life of the town. Small cities of the living and of the dead spread toward each other, separate tides on a merging course.

We walk between rows of stones. There is a pattern here. The older stones at the centre of the hill stand proud on the highest point. Those of obvious and early wealth have the best views. But time has brought greater equity to death. Where once the living imposed familiar social order on their dead, with final resting points determined by status in life, now rich and poor alike share the same space. In recent years, final resting places are dependent on the year of death, not on income in life.

This equity feels serene. Here are the great and the good, the significant and the small. All alike in their irrelevance, together in one place at their end, on this hill at the edge of an island on the edge of the Earth. Each of these people had, at some point, mattered to someone. And all would be forgotten, as those who remembered joined them in earth.

It’s only now that I wonder what conclusively not finding a grave would have meant. That her brother was incinerated at the hospital like a piece of medical waste?

We’re less than half way around when my mother says she wants to stop. We haven’t find what we’re looking for and we don’t really know where or how to look. Harsh winds and salt air have weathered even recent named into obscurity. We haven’t found any children’s graves and aren’t sure, if they’re in a separate section, where they might be. I suggest we phone the district council to ask if they have a record of her brother’s grave, but my mother has had enough. She doesn’t want to know any more. I’ve pushed her into picking at this scab and it’s too raw.

Instead, we retreat back to town and back to Osler’s Bakery for a proper New Zealand pie.

It’s only now that I wonder what conclusively not finding a grave would have meant. That her brother was incinerated at the hospital like a piece of medical waste? I’m relieved now that we stopped looking when we did.

As we drive out of Wairoa, something lifts. We’re both lighter. My mother is the best version of herself, chatty and engaging, opening up to strangers at every cafe and every campsite, telling everyone who enquires about the purpose of our journey.

Low sculpted volcanic hills wrap themselves slowly around us as we drive. Denuded of their forest covering they are cloaked instead in a hazy shifting beige and green—grass deadened by a century of grazing, In the evenings, a hard, clear light draws out the bones of the land. The folded hills, black rocks, every tree and shrub is cast into relief. Each turn opens new shapes of twisting upthrusts of rock, steep-sided hills marked by tier upon tier of sheep tracks that ripple down and around the hills.

My head spins with every back and forth coil, as I guide the wheel tight into each bend, winding between diminutive hills. On short downhill stretches, where I can see the road unfold beneath her, I take the racing line, delighting in these small moments of efficiency and tiny rebellion.

The car we’ve hired is the cheapest available. It’s small, used to be white, and rattles when it gets above 50 mph. We name it Pig. On the undulating roads, when we’re stuck for long durations behind artic lorries and the only passing lanes are on short uphill stretches, we urge Pig to his limit as he struggles to overtake with a chant of:

“Pig! Pig! Piggy Wig! You can do it, Pig-pig-pig!”

We rarely make it but sometimes get as far as driver’s cab for long enough to catch a bemused expression, before we have to drop back down into second position again.

With us is Bear. A small mascot who sits on the dashboard and narrates anything that either of us doesn’t want to say to the other directly. Bear is a safe vessel for expressing our frustrations; my primary frustration being that she keeps hijacking my bear to make him say what she thinks.

The phrase “Bear thinks …” begins to grate on me.

“No he doesn’t” becomes my stock response.

But our arguments are relatively light and few. There’s one thing though, that begins to bother me more than the hijacking of Bear’s thoughts. It’s my mother’s insistence, in every conversation, on talking about “her” family. Every ancestor is referenced in relation to her. Her grandfather. Her cousins. Her aunt. Repeatedly, I remind her that this is my history and my family too and she rolls her eyes and says.

“Yeah, I know.”

And continues to say it.

Until, driving through what feels like the hundredth kiwi orchard, I pull the car to the side the road, sit on the grass verge and refuse to go any further until she acknowledges that this is also my family story. Which she does. And is surprised at my upset. But she makes a point, in her next two conversations with strangers, of pointing out that that this is our family research trip. And I realise what a ridiculous verbal mashup I’ve forced her to adopt. I see the confusion in her face when she tries to talk about our grand slash great grandfather, our first slash second cousins, our aunt slash great aunt. Gradually, she slips back to the default and I let it go.

But an idea begin to fall, very slowly, into place.

London, 1989/2000

Some memories are tied forever to specific places, smells, flavours, objects. They return unbidden every time I pass a certain corner or catch the warm vanilla scent of orange blossom. Often, I don’t catch the whole memory, only a hint of something heavy or joyful as it flits through my consciousness.

Etched into my memory of the path across Wandsworth Common is the irritation of persistent piece of grit in my shoe as I trot to keep up with my mother’s lengthened stride. Unable to stop and clear out the dirt, I can feel the tiny stone wedge itself between my toes, wearing its way through the thin cotton of my sock. I am always just a little behind, alternately spilling my heart and throwing recriminations, begging to be heard. I am fourteen.

"You’re so busy trying to prove you can survive without dad you don’t see me. You don’t see me or Sam. You don't see either of us.”

She stomps on—always a pace ahead, refusing to allow me to reach her. Her face is hard and cold and she won’t look at me. I run a fragile line between compounding my rejection and finding a chink in my mother’s emotional armour—a way into her heart. I can’t stop. I’ve started and know that the moment I give up I will be more alone than ever. As long as I keep trying, there is hope.

Ten years later, we are walking a different path. I’m accompanying my mother to the station for the first leg of her journey to her new home in Oxford.

It’s been a stressful time for us both. The two-up two-down house which she owns and I rent from her is in the middle of major renovation. I’m living in a building site, paying rent on a house that is barely habitable. I’m sharing that house with Mick, the 55 year old builder she’s imported from Oxford and who’s now living in the second bedroom, directly opposite mine.

She drags herself toward the station, scraping her toes like a reluctant toddler, listless and agitated in turns. I listen intently as she talks rapidly but can make no sense of what she is saying.

During the day, I’m working in central London while Mick makes negligible progress on the building work. At night, I cook for him in the temporary kitchen he’s created in back of the two downstairs rooms, clean up while he watches television in the front room, then buy myself in my bedroom. At night, we are separated by only a three-foot landing and two flimsy wooden doors that neither lock or shut properly. There’s no functioning kitchen or bathroom, he’s eating everything I buy on my meagre wage, and I’m pretty sure he’s going through my room during the day.

But I’m trying to be understanding. I know my mother is struggling. That Mick’s slow progress is frustrating her as much as me. She’s never been good at project management but she refuses input from anyone else, or to consider that her approach may not be the most rational, sensible, or financially or emotionally efficient. But her behaviour and her conversation are more erratic than usual.

She drags herself toward the station, scraping her toes like a reluctant toddler, listless and agitated in turns. I listen intently as she talks rapidly but can make no sense of what she is saying.

When she says something about demons dragging her towards the river I clutch her arm, pulling her stationary.

“What are you talking about?”

“Nothing. Forget it." An exasperated sigh. “ I shouldn’t have told you. It doesn’t matter anyway, I’m going away so it doesn’t matter.”

"What do you mean? Where are you going? What demons?“

“It doesn’t matter. It was my own little secret. Forget it. I’m probably not going now anyway. You’ve ruined it.”

She pulls her arm away. I let it drop and turn my back. I start to walk home, grit scouring my feet, tears burning my heart.

“Miranda?” My mother’s voice behind me is plaintive. “Don’t leave me. Don’t be so cruel.”

But I have nothing to say. Nothing to give her. I have been left too many times—been threatened with loss so often that I have no other way of dealing with my mother’s madness. Is this the first time I see this is bigger than me? The first time I wonder if I can’t fix this?

Hawkes Bay, New Zealand, 2005

My mother is giddy with excitement when we get to Mahia and I quickly understand why. The beach is a monochromatic wonderland. Gentle turquoise breakers roll over black volcanic sand. Multiple strandlines are littered with bleached acres of driftwood. Whole white trees lie naked all along the sand; a horizontal driftwood forest, ten thousand small and private deaths, rearranged with each Pacific tide.

We take off our sandals but I quickly put mine back on as the heat that penetrates through my soles is blistering. I take them off again when we start walking. As long as my feet are moving, the scorching can’t catch up with me. I spread the heat across every walking surface—dancing toes, sides of feet, hot heels.

We’re the only people on the beach.

Under my feet, I feel the ground ripped from beneath me with every rush of the undertow. I don’t speak. I just listen quietly as she fights with her memory. Trying to separate fact from fantasy.

When we stop at the waters edge we stand in the shallow breaking waves and I dig my feet below the burning surface grains into cool sand. Waves break over my feet and salt catches in sand scratches, raising welts on my sunburned skin. The light here is so dazzlingly bright it blinds. A thousand points of light shift on the sea’s surface are caught and fractured by softly breaking waves.

“I thought there was a house up there.”

I follow my mother gazes up to her right, toward a small bluff that defines the edge of the beach. She looks perplexed. Confused.

“I had a plan. When Mick was fucking up the building works. I was going to come here, to the house on the point. But—there’s no house.”

I search the hill above us with my eyes. It’s covered in bush with no break that might indicate a dwelling. Not even a dip where regrowth might have occurred. So this is what she meant. This is where she was going to come when the pain was just too much and the demons were dragging her into the Thames.

Under my feet, I feel the ground ripped from beneath me with every rush of the undertow. I don’t speak. I just listen quietly as she fights with her memory. Trying to separate fact from fantasy.

And I picture her then, escaping the horrors of daily reality. Living out the rest of her days in this perfect paradise. And I wish there really was a house. A house where she could live in peace with herself and from where she could live out her dream to come back to the sea. A house where I could visit and share what we loved independently and together.

The sea. The birds. Music. Silence. Words.

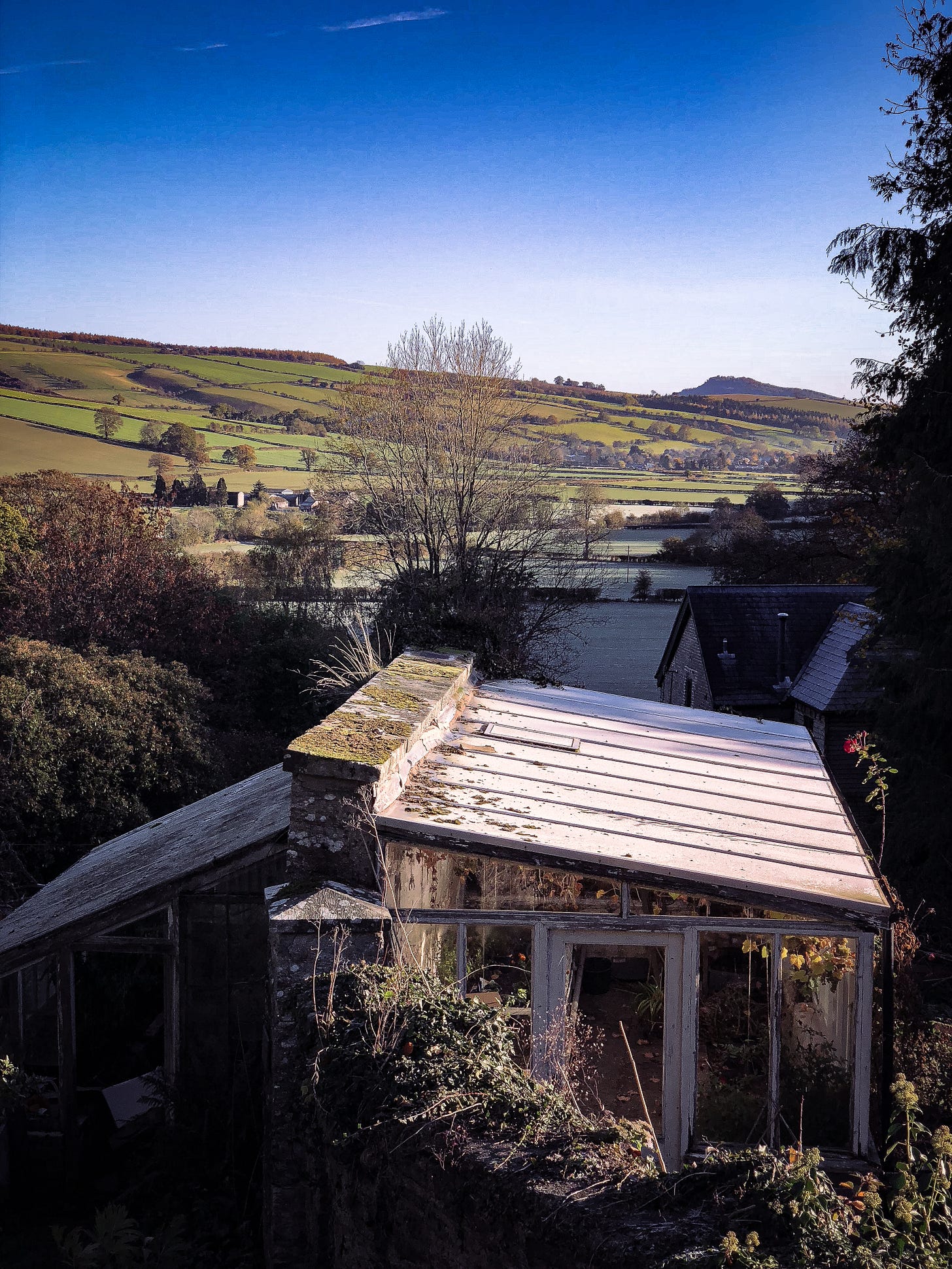

Shrophire, 2018

I came out of the tutorial peppered by grief—walked uphill away from the house, along a muddy lane and stood beneath the skeletal branches of a spreading oak tree overlooking a valley.

I wondered if I should go back. Should I go and ask him—was he telling me to stop? Was he telling me to forget about my mother’s story and find only my own. Because I didn’t know how to do that. I didn’t know my story. I didn’t have a story.

And then, staring up at the bare branches of the ancient tree that spread itself over both path and field, I clicked with relief. He wasn’t telling me to forget or to stop anything at all. It was an observation, not an instruction. He was just pointing out the irony. It was an irony I needed someone outside of me to show me.

— the parts of myself I shared with my mother, I also shared with my brother, my grandparents, and with many of my friends. I shared them with the people I’m drawn to, people with whom I have no history or shared bloodline.

I thought I had separated from my mother. In reality, in trying to find my own identity separate from hers, I had thrown away my own core. I had spent years trying to find a version of myself that excluded anything and everything I’d ever been told about myself by my mother. Once I’d discarded everything I’d inherited from her, learned from her, been told by her, enjoyed with her, all of our shared passions and interests, I had been left with a brittle, slightly bitter, and empty husk.

But the parts of myself I shared with my mother, I also shared with my brother, my grandparents, and with many of my friends. I shared them with the people I’m drawn to, people with whom I have no history or shared bloodline. Just because I shared some aspects of my story, my interests and my identity with someone else, didn’t mean I was someone else.

I needed to find my own story. I needed to find myself, with and separate from her. To do that, I had to let go of another story—the one that said everything I saw in my mother was her invention and her possession—that if was part of her, it couldn’t also be a part of me.

I had to allow myself to pick up and begin to enjoy the things I loved again. Music, art, ecology, walks in the woods and by the sea. Gardening. Growing. Writing.

When I left Arvon, I avoided the motorways and drove instead along A-roads and country lanes. I passed through the Malvern Hills, along a long ridge that overlooked a wide river valley and felt my heart lift and my world expand. It was a bright November day, the very best that winter can offer.

I travelled across unfamiliar country, actively noting and appreciating every landscape change. I slipped into Sussex and home with barely a whisper. Only the smallest, slightest hint of sadness that I was leaving that big wide world behind.

And another hint. This time of anticipation. For the journey to come.

The names and identifying characteristics of individuals and places have been changed.

I’m curious to know how many of us lose our own stories in those of other people. How many of us are so focused on the stories we’ve inherited, we forget to pay attention to our own? Also, how a chance remark can unlock a whole other view of our reality.

Does anyone recognise this?

I got excited when I saw in your notes that it was “a long read’ and came directly here. I read the final passage three times such is its depth. And when you spoke about the drive home from Arvon and feeling those whispers of anticipation for the journey ahead - the journey back to self - I cried.

Reading about your mum’s experience growing up and the unconscious loss and trauma she experienced whilst even just still in the womb cut me to the quick. Never ever, of course, to excuse someone’s bitterness and ability to inflict such cutting pain - which your mum has clearly had the gift for. Your ability, however, to see your mum as a victim of victims is profound.

I also love what you say above about leaning into the pain of our own experience enables us to see the intense pain that others carry and have not been able to process. - (and gives us the boundaries to be able to say “No more!” to their projecting their own pain).

Och, You, Miranda, are an incredibly gifted writer.

Incredible read. Painful, evocative, thought-provoking and uplifting.

Love how you jump between different times/places in this essay, Miranda. And how your mother's voice stubbornly lingers around throughout it all. So easy to become enslaved by narcissistic voices like that. Great you're writing about that journey though.